A Higher Plane: The Art of Colin Goldberg and Techspressionism

Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky

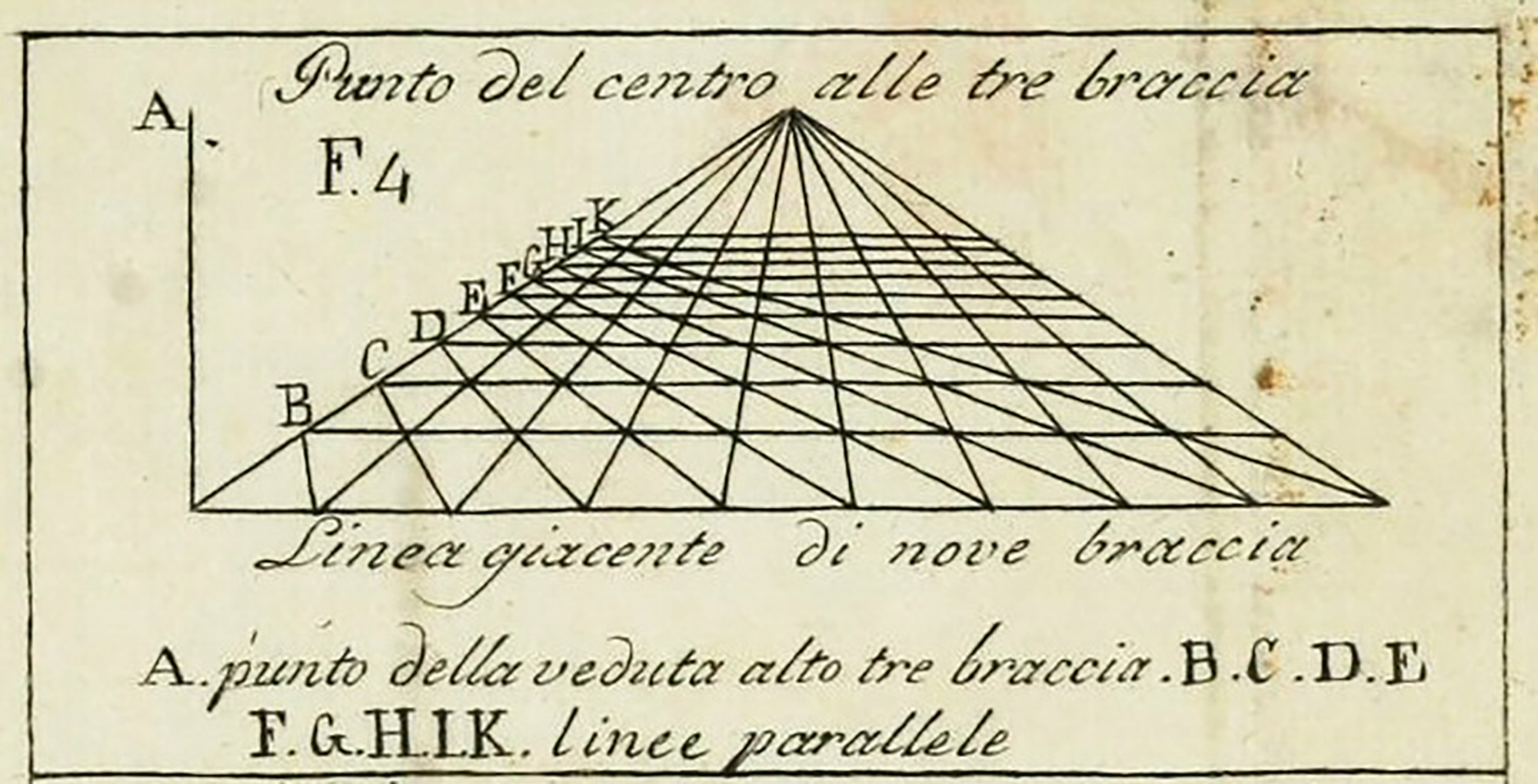

Leon Battista Alberti – De pictura . Florence, Italy 1435 AD

It’s all about dimensionality. Whenever we look at a piece of art, there’s a process of legibility. We read the surface and inhabit the perspectival architecture. Move into the world the piece evokes. Raymond Kurzweil conceptualized the singularity as a moment when all aspects of culture move into an exponential growth cycle. This cycle creates an infinite momentum driven by technological change and innovation. These days, we live in a time that one could argue is “post” singularity. There are limits. But there are no limits.

To remix Kurzweil when he paraphrased the 19th Century philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer: “Everyone takes the limits of his vision for the limits of the world.” From Schopenhauer to Kurzweil’s Age of Spiritual Machines, we see a link that characterizes the phenomenological world as the byproduct of blind noumenal will.

We see, experience, and lose ourselves in the immediacy of the sheer volume of information we are drowning in. In doing so, we seek new methods for navigating the ocean of informatics we have generated in such a short amount of time. Human history in the arts is always paradoxical.

This leads me to the art of Colin Goldberg and the Techspressionist movement. In theater, “breaking the fourth wall” means that you, in the audience, have become part of the narrative. Think of the city as a new kind of narrative with overlays of data and abstract from there.

Call it the theater of code. I’m sure we’ve all experienced that moment where the uncanny properties of digital media and personal subjectivity have felt eerily blurred. It’s that sense of latency when you feel the invisible forces of information around you, such as cell phone signals and the coercive algorithms of platforms that are engagement engines. There is a sense of Déjà vu – the impression that we have already experienced something even when we know we never have.

It’s this scenario that Techspressionism explores. In our time, we have seen the most consequential legacy of the Renaissance: zero-point perspective – the non-linear technique that gives the illusion of depth when no parallel lines are in the image. This model has become the most potent tool for dimensional projection in digital media. Think about it.

Leonardo da Vinci – A map of Imola Imola, Italy 1502 AD

Several hundred years ago, Leonardo Da Vinci took zero-point perspective to the highest level. When we look at his works, such as the map of the Italian city of Imola (1502 AD) that was commissioned by Cesare Borgia (yes, the Borgia family… archrivals of the Medici) to use for battle plans, Da Vinci did something radical – he imagined the city from above. This is called axonometric projection. A modern example of this is Google Maps. The thing is – Da Vinci did it 500 years before satellites existed.

Generally, this represents a kind of ichnographic map that predates our modern cartography and transforms the map from an exercise in imagining the city to making it an informational asset – again, hundreds of years before satellites.

Modern computer graphics concepts such as vector art and bitmap images are derived in part from the history that Da Vinci helped create.

Let’s fast forward to our current moment. Colin Goldberg is an artist with a rich and diverse background. He was born in NYC to parents of Japanese and Jewish ancestry. The artist’s work explores the intersection of physical space and the urban “legible” landscape.

From audiovisual blockchain-based works to augmented, virtual, and extended realities, we see a hunger to explore the possibilities of reimagining an invisible landscape.

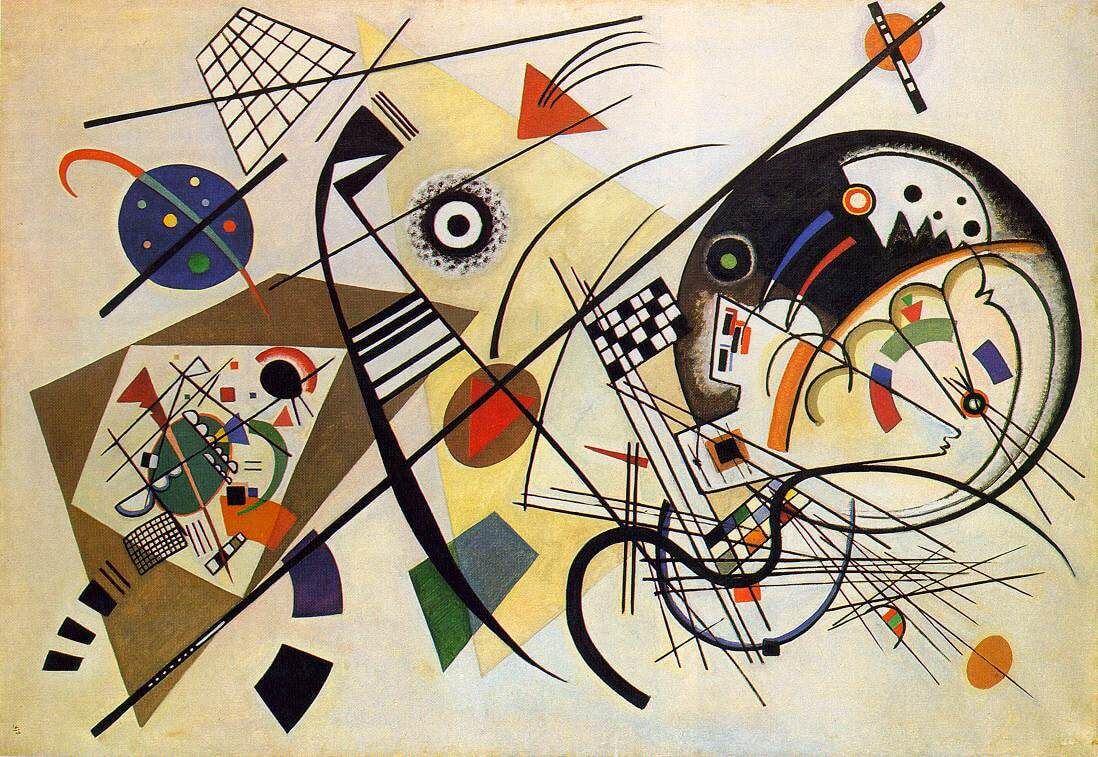

The works in this book are metaphors of code. They linger at the intersection between physical space, code, and culture. Goldberg’s Metagaphs relate to the works of earlier artists who explored abstraction, such as Kandinsky, who stated:

“Abstract art places a new world, which on the surface has nothing to do with ‘reality’ next to the ‘real’ world.”

Transverse Lines, 1923 by Wassily Kandinsky

The Techspressionist movement has echoes that resonate with many previous generations of artists. However, the amorphous nature of the movement is radically open, embracing the tools of our time – generative art, NFTs, AR, VR, XR-based geo-tagged work, stochastic processes, Markov chains, and machine learning. Machine learning is the basis for large language models (LLM) such as OpenAI, Google’s Bard, and Facebook’s LLAMA. These platforms are based on highly complex algorithms that scrape data from the internet – but with a human (or perhaps more than human) twist.

No human being is on the other end of a predictive text engine when we type on our cell phones – a commonality shared with the generative tools used by many of today’s digital artists. That’s cool. But what about the deep learning processes of the software that allow this creativity to thrive? There hasn’t been another art movement that has embraced the complexity of these systems in the way that Techspressionism has. I like that. It’s all new and old at the same time. And that’s OK.

Goldberg and the milieu of artists he has worked with in formulating Techspressionism have their work cut out for them. These artists include technology art trailblazers such as Anne Spalter, who developed the first digital fine arts courses at RISD and Brown University in the 1990s, and Steve Miller, an early pioneer of the Sci-Art movement. These two artists, from a different generation than Goldberg, each have practices that overlap with his work in Techspressionism.

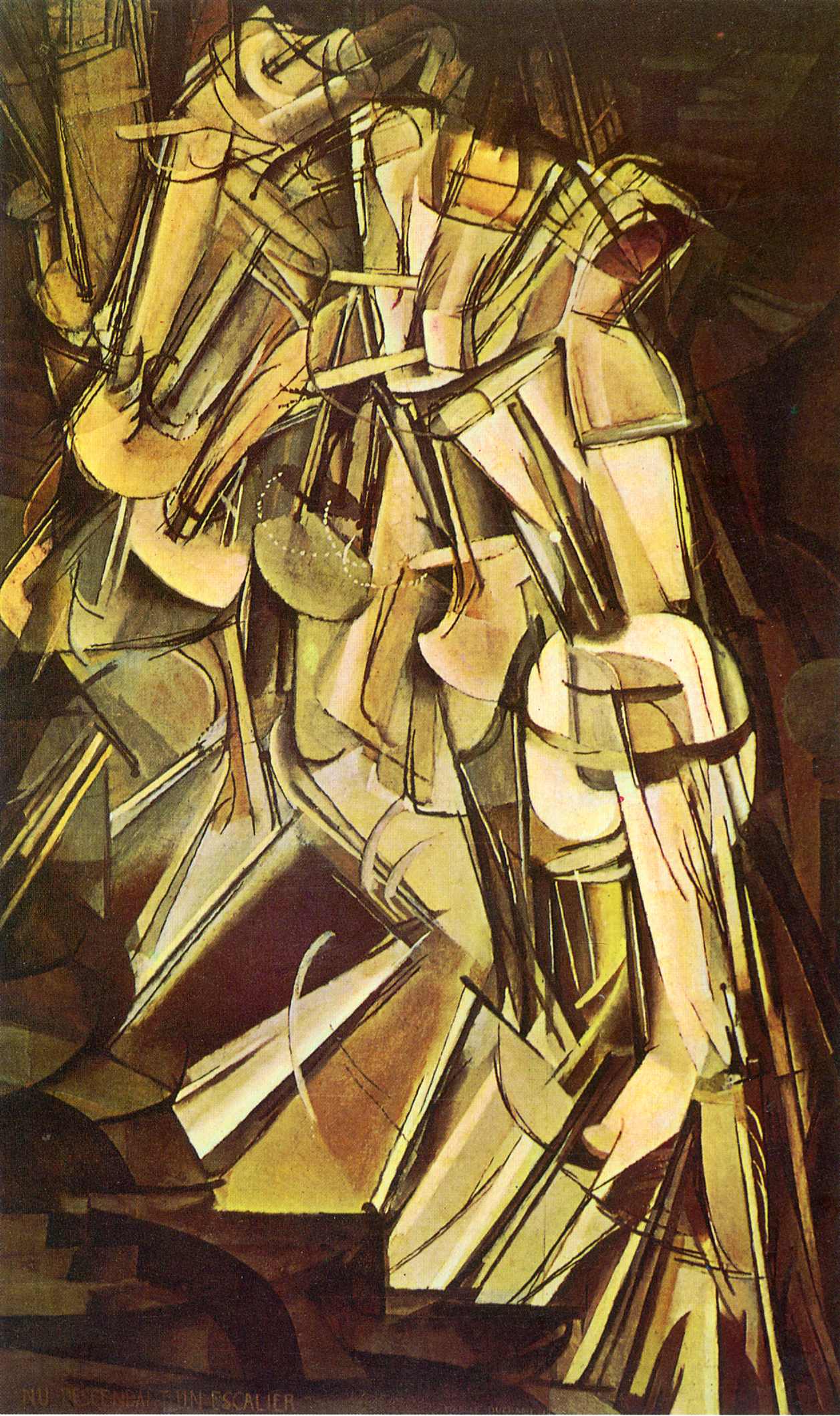

Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, 1912

by Marcel Duchamp.

Many established artists’ works resonate with what you will see in this book – sometimes with ideas, sometimes with images that look like they were in the same Pinterest post. But they aren’t. Think – Rafael Lozano Hemmer, Bridget Riley, Paolo Cirio, Ryoji Ikeda, Refik Anadol, Sol Lewitt, Nam Jun Paik, Wassily Kandinsky, Marcel Duchamp, Robert Rauschenberg, Hilma Auf Klimt, Kazimir Malevich, Charles Gaines, Peter Halley… the list of ancestors is wildly varied. But that’s the point. Think of previous art movements that are tech-adjacent.

Surrealism, Vorticism, Futurism, Cubism, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Constructivism, Abstract Expressionism…. You name it. The intriguing thing is that today, these movements have become additive stylistic properties.

These properties may reside in a software filter on Instagram or a web-scraped style of a generative AI platform. That leads me to the fun side of this – imagine an art movement that is a palette made of other palettes. An instrument that is of many other instruments.

Technology has always been a radically unstable field. What works today will not work tomorrow. Ask Nam Jun Paik! But on the other hand, it’s that willful sense of experimentation that makes this movement so intriguing. I hope you can experience this book with that in mind.

One of the most critical insights that Kandinsky had was this:

“There is no must in art because art is free. Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, and the soul is the piano with many strings.”

What new approaches can allow us to navigate the ocean of information we’ve created in these dystopian times of data surveillance and ubiquitous computing? How can artists reimagine the new worlds of information that churn out of the labs of the major corporations that dominate informatics?

These are the questions that nobody has a grip on. And that’s OK. It just means we need to think of life as a continuous learning process. And that means always looking at new art. Techspressionism asks a question that we can’t answer. Just keep an open mind and see what the question evokes. That’s what art, maybe, is all about.

Enjoy!

Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky

Livingston Manor 2023

ABOUT DJ SPOOKY

Paul D. Miller, aka DJ Spooky, is an Artist in Residence at Yale University Center for Collaborative Arts and Media (2023-2024, extended). He is a composer, multimedia artist, and writer whose work engages audiences in a blend of genres, global culture, and environmental and social issues. Miller has collaborated with many notable recording artists, including Ryuichi Sakamoto, Metallica, Chuck D from Public Enemy, Steve Reich, and Yoko Ono. His 2018 album, DJ Spooky Presents: Phantom Dancehall, debuted at #3 on Billboard Reggae.

His large-scale multimedia performance pieces include Rebirth of a Nation, Terra Nova: Sinfonia Antarctica, commissioned by the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and Seoul Counterpoint, written during his 2014 residency at the Seoul Institute of the Arts. Miller’s multimedia project Sonic Web premiered at San Francisco’s Internet Archive in 2019. He was the inaugural artist-in-residency at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s The Met Reframed, 2012-2013.

In 2014, Miller was named National Geographic Emerging Explorer. The following year, he produced Pioneers of African-American Cinema, a collection of the earliest films made by African-American directors. Miller’s artwork has appeared in the Whitney Biennial, The Venice Biennial for Architecture, the Miami/Art Basel fair, and many other museums and galleries.

His books include the award-winning Rhythm Science, published by MIT Press in 2004; Sound Unbound, an anthology about digital music and media; The Book of Ice, a visual and acoustic portrait of the Antarctic; and The Imaginary App, a book on how apps have changed the world. His writing has been published by The Village Voice, The Source, and Artforum, and he was the first founding Executive Editor of Origin Magazine.

ABOUT | ARTIST | COMMENTARY | FILM | BOOK | NFTs | MAILING LIST